Though not far as the crow flies from Ireland’s west coast towns of Doolin and Galway, the treacherous moods of the wild Atlantic have long kept the people of the Aran Islands close.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Today, you will still hear Irish being spoken on every corner, but until the first tourists started to arrive in earnest, the history of the islands was shaped by isolation.

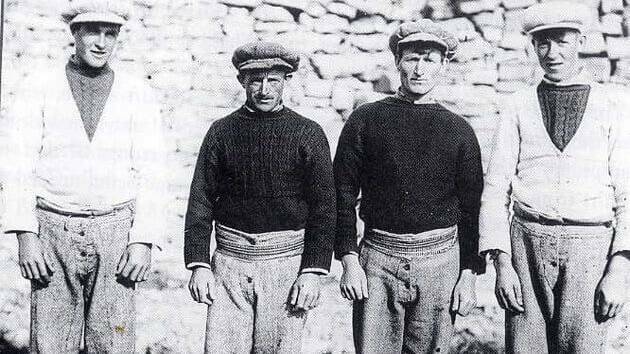

It’s been home in turn to Bronze Age warriors, pagan Celts and Catholic saints, and later the small Gaelic speaking fishing community who married their fortunes to the harsh environment.

Their reliance on the sea protected Aran Islanders from the famine that decimated much of Ireland during the mid 1800s. Today, as well as the tourists, students come to the islands during the summer for Irish language lessons.

There are three Aran Islands, and I visited the largest, Inis Mor, where the ferries are met by pony trap drivers offering to take visitors for a spin back in time.

The island is dotted with the ruins of bee hive huts and crumbling churches dating back to the tenth century, but most of the day trippers are here to see the most famous of the beautifully intact stone forts, Dun Aonghasa.

In ancient times this hill fort housed a thriving society of late-Bronze Age elites, and the walk up to where it looms on a hill at the cliffs’ edge has to be one of the “must do” experiences for visitors to Ireland.

The fort receives up to 1,000 visitors a day and like many, I opted for a hired push bike to take in the scenery on the seven km ride from the wharf to the fort.

About half way along there is a seal colony, where a family of giant seals heave themselves on and off rocks, bellowing to each other.

I was not a day tripper, so peddled many miles around the island, exploring only some of the natural wonders; strange rock formations with names like the Serpent’s Lair, the Worm Hole and the Puffing Hole along with more forts, cemeteries and churches.

The countryside is criss-crossed by stone walls, ponies graze in fields freckled with daisies and the pale blue Atlantic can be seen from almost everywhere.

The people are kindly and chatty and the main village, Kilronan, is tiny and traditional, with bars and craft shops selling the famous Aran knitwear.

The Aran sweater, which took weeks to knit by hand, is steeped in myth. The intricate patterns were once jealously guarded and are said to reflect the ancient symbols and patterns found in the fields, farms and folklore of the islanders.

Another controversial belief is that individual patterns were specific to certain clans, which, in a not so fun fact, were used to help identify bodies of drowned fishermen when they washed up on the beach.

The sweaters were originally hand-knitted with unwashed and undyed wool – the lanolin making them water resistant and warm for the wearer.

In the 1950s, Aran jumpers appeared in Vogue magazine, and famous Irish expats, folk singers, the Clancy Brothers and Luke Kelly began wearing them onstage. Soon orders were flowing in, and at one point more than 700 hand-knitters across Ireland were struggling to keep up with demand.

Recently, orders for the sweaters have gone through the roof again,after Hollywood hunk Chris Evans wore one in the movie Knives Out.

A visit to the Aran Islands uncovers the layers of Ireland’s ancient history and offers a taste of a traditional community dependent on the rugged environment for survival.

Now survival might be more tied to the tourists boats coming in and out of port and the sales of the once functional fishermen’s sweaters that provided protection from the harsh Atlantic elements.