As a young boy regularly riding the Manly Ferry across Sydney Heads, I was captivated by the derelict old brick and sandstone buildings perched atop the rocky cliffs of North Head. Was it a hideout for stowaways from faraway lands? If only. Or was it a long abandoned holiday resort? The imagination ran wild.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

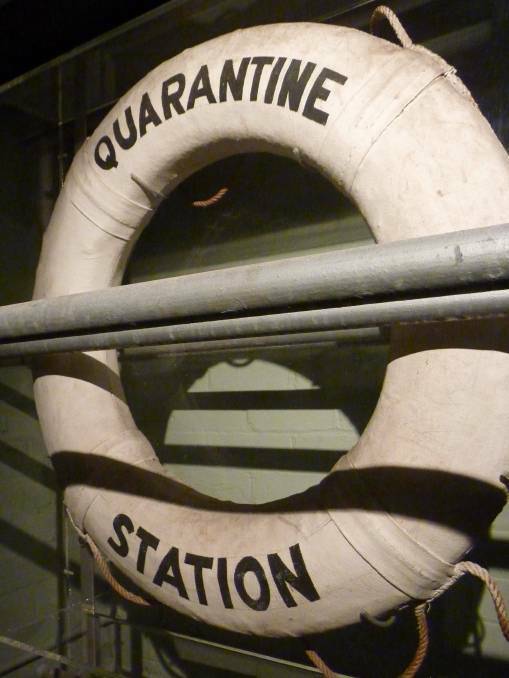

Years later, I discovered it wasn’t anything quite so fanciful, rather this hotchpotch collection of more than 60 buildings was the remnants of Sydney’s original quarantine station.

To protect Australians from becoming sick, from 1828 to 1984 migrant ships arriving in Sydney with suspected contagious disease were ordered to stop here and to offload their passengers and crew into strict quarantine.

Most of those quarantined during the station’s first 100 years of operation had been forced to endure long voyages from the other side of the world on disease-ridden ships. These included the English barque Lady MacNaghten which, when it arrived from Cork in 1837, had already lost 54 passengers to typhoid. Thirteen more died after arrival at the Quarantine Station in what was described as ”truly appalling conditions with a sense of misery, wretchedness and disease present everywhere”.

While reports abound this week of some Australians begrudgingly quarantined due to COVID-19 grumbling about the conditions cooped up in a five-star hotel room, quarantine was a far more traumatic experience for those who ended up at North Head in the 19th century. For 40 days and 40 nights (no doubt harking from biblical rather than medical origins), newly arrived migrants and crew would be ordered to ”do time” – many isolated from family. Some say the Australian spirit was shaped by experiences of hardship and friendship forged here.

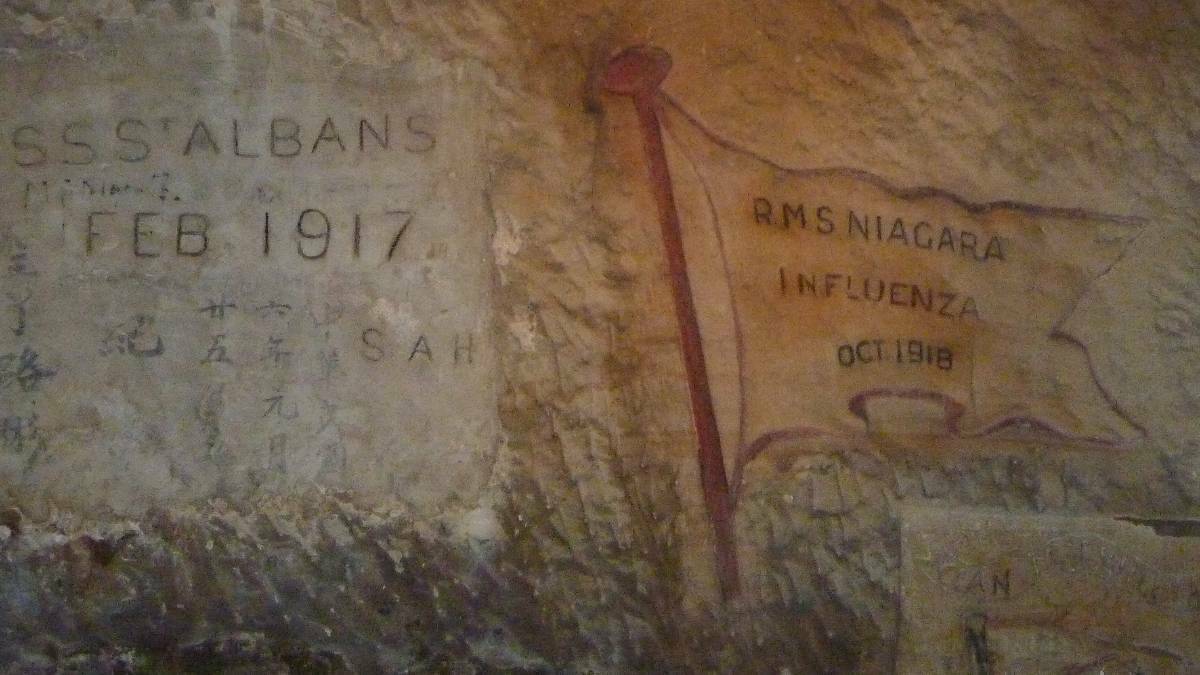

Today, scattered throughout the sprawling 30-hectare precinct, are many tangible reminders of when the station was operational, including historic graffiti etched into all manner of surfaces, including tree trunks and naturally occurring sandstone overhangs. One of the clearest inscriptions depicts the RMS Niagara which unloaded a human cargo here in 1918 during the Spanish Influenza pandemic.

First-hand anecdotes of the pandemic, collated by historian Richard Collier, recall the devastation which unfolded on board after the ship left Vancouver and sailed towards New Zealand.

”… it spread through the ship like wild fire and … 80 per cent of the crew and quite a number of the passengers went down with it. They … had to use the music room as a hospital with mattresses all over the decks.”

The plight of those on board didn’t improve when the RMS Niagara arrived in Sydney, with reports most of the doctors at the quarantine station succumbed to the flu, leaving ”anyone who was still able to stand up” to tend to new arrivals. The headstone of Annie Egan, one such carer, who died in December 1918, still looks out towards the ocean and poignantly reads, ”Her life was sacrificed to duty”.

Also near the wharf is the old shower block where disembarking passengers would be hosed down and scrubbed while their luggage was hauled uphill (after it was washed and fumigated several times) to hospital-style accommodation blocks.

While tens of thousands survived their ordeal at the Quarantine Station, more than 600 people never left. The station’s first cemetery was closed due to the smell of rotting corpses after 16 years of shallow burials in unusually rocky ground.

A report by the then clerk of works, cited in Jean Duncan Foley’s book In Quarantine, A history of Sydney’s Quarantine Station 1828 – 1984 (Kangaroo Press. Kenthurst. 1995), describes the rationale behind the closure of the graveyard more eloquently.

“Just below the Healthy Station and so conspicuous that Parties cannot go out to take the fresh air, without being reminded of the mortality of so many placed in similar circumstances to themselves; besides which the water which supplies the Station trickles through the Graveyard on one side and the association is anything but agreeable.”

Given the site’s morbid past, it’s not surprising the precinct has a reputation for being haunted. Apparitions and unexplained behaviour thought to be the spirits of distraught, sick and lonely internees have been reported by a hoard of credible eyewitnesses including nurses, park rangers and even previously self-confessed sceptics.

When, 15 years ago, the site was being converted into a modern hotel and conference centre rebranded as the Q-Station, Kelly Giblin of Paranormal Australia was worried these voices from the grave would be forgotten.

“If there is significant development on the site, the atmosphere of the place will change and literally scare the ghosts away,” she warned.

Kelly needn’t have been worried, for the Q-Station well and truly embraced it’s haunted history, purposefully cashing in on its grisly past, promoting it as a must-see destination for paranormal investigators with near-nightly offerings of spooky tours and spirit investigations.

While COVID-19 has temporarily put an end to these after-dark experiences, in a bid to stay afloat, the Q-Station has re-invented itself, offering self-isolation packages in a range of accommodation including self-contained cottages, cleverly billing them as ‘We’ve been in Quarantine since 1828″.

One wonders if in 200 years’ time, future visitors will uncover graffiti scratched into the floorboards of these cottages by those hunkered down in quarantine during the Great Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020.

Talk about turning full circle.

Q-Station Isolation Packages:14-night minimum stay. Grocery pack delivery to room. From $100 per night in the former first- and second-class accommodation to $175 for two-bedroom apartments in the former hospital. Limited room servicing. To book, call 02 9466 1500 or email: h8773@accor.com