At an enormous termite mound, I am transfixed by the small race against time playing out in front of me. There’s a hole in the exterior and tiny workers are rushing to close it, one grain of sand at a time. Meanwhile, ants are crawling up and down, trying to find a way in, tasty termites on their mind.

Create a free account to read this article

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

That this drama, unfolding on a stage just three metres high, is so engrossing gives you an idea of how much must be happening across the entire 1500 square kilometres of Litchfield National Park. Millions of interactions between plants and animals, some as tiny as an ant hunting a termite, some as huge as thundering cascades carving a rock. But they all fit together to create distinctive Northern Territory landscapes, something Rob Woods tells me he wants to highlight on his Ethical Adventures tours of the park.

“The idea is not just to take them as individual elements – this is stone country, this is a waterfall, this is wetland – but try to link them up and say ‘this joins onto that’, and try to create within Litchfield the map of how that ecosystem works,” he says.

Simply looking at a map doesn’t do justice to Litchfield National Park. Although it’s just 1.5 hours’ drive from Darwin, it has the remote feel of the outback. The iconic vistas of the park are its red rock escarpments with waterfalls crashing into pristine swimming holes, but there are also patches of rainforest, wetlands, bushland, and near-deserts. On the day I visit, bats hang from trees, a frilled-neck lizard runs across our path, rock wallabies hide in the bushes, and a (freshwater) crocodile sighting closes one of the waterholes.

Because Litchfield National Park is so close to Darwin, it’s a popular day trip for locals, who come to cool off in the beautiful swimming areas you’ll find beneath waterfalls or the creeks that flow from the wetlands across the elevated sandstone plateau (nature has a way of making pools more inspiring than any hotel). But there are plenty of other areas to explore, with walking trails, scenic lookouts, heritage sites, and four-wheel-drive trails.

Knowing all of these options is something Rob Woods prides himself on, and his tours are different each time, changed slightly depending on the crowds, the weather, or the interests of guests. When we arrive at the park quite early, we go swimming straight away at Florence Falls and have it almost to ourselves, floating serenely with just the sound of the waterfall. But after a bit of a walk, during which Rob points out interesting animals and plants, we decide to skip nearby Buley Rockhole because it’s already getting busy.

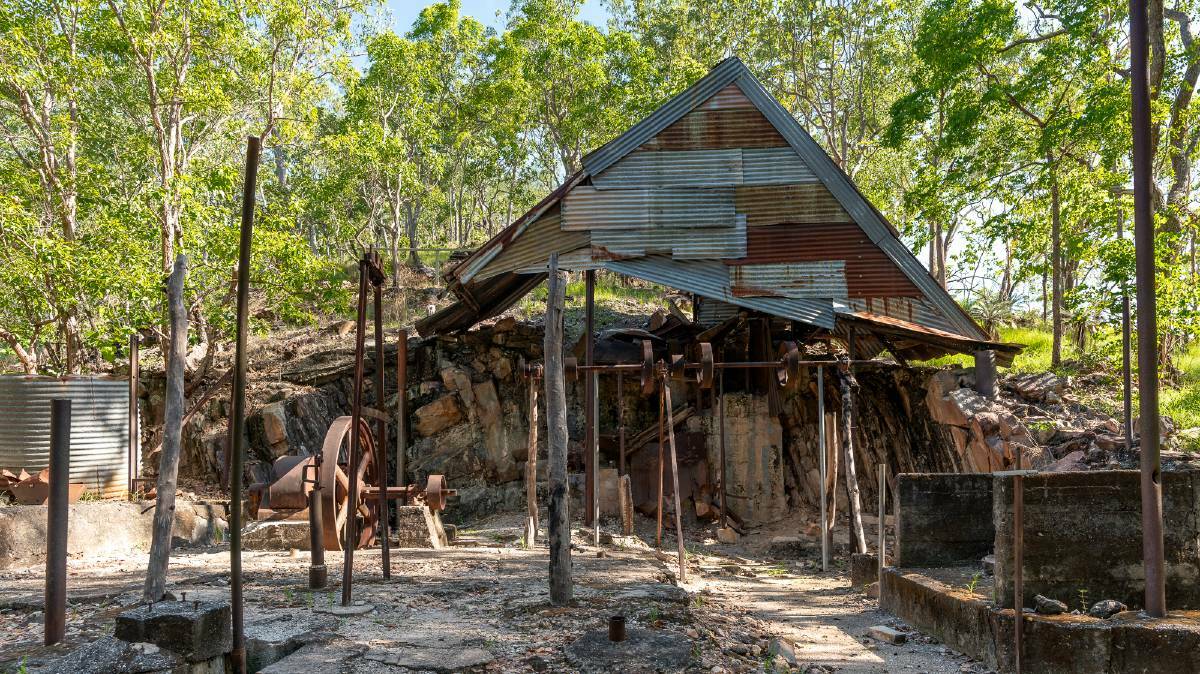

Of course, we stop at Wangi Falls to see the enormous streams falling down the sheer red cliffs into the expansive pool, but otherwise Rob takes me to lesser-known areas – a quiet walk along the river to a deserted swimming spot at the Cascades, the towering magnetic termite mounds that always incredibly line up along the north-south axis, and an old tin mine at Bamboo Creek that was established in 1906 and abandoned about 50 years later. Walking along the path around the mine site, the path glitters in the afternoon sun from all the mica in the dirt, while a blue-winged kookaburra calls out – not the maniacal cackle I’m used to from its laughing cousin. It strikes me how different things here are. Not just compared to Australia’s southern states, but to where we were just hours ago in another part of the park.

“Hopefully you’ll realise it’s more than just a swimming hole,” Rob says. “It’s more than just a place to do in a day because you’ve got a day to spare. You can go out and sit and look at things and think about how they link up.”

The flexibility and small groups in Rob’s tours are not its only points of difference. The name of his company, Ethical Adventures, is a big clue to the most important aspect of what he does. To Rob, being “ethical” is different to being “eco”. He believes that part of his business model should include advocacy, and he is active in environmental campaigns to change behaviours and policies of authorities and other tourism operators.

“Ecotourism is a great concept to start with,” he explains.

“But where they fall short is they’re not actually doing anything about the threats to those places. We need to mobilise the tourism industry to start advocating for protections for all these places where they actually get their money and welfare from.”

Just one person and one action can make a difference. We are just like those tiny termites, adding a grain of sand at a time to close the breach, protecting their whole mound and community from the killer ants. Our ecosystem is not as small but, relatively, perhaps it’s not so different. Right now we cherish Litchfield National Park for representing the best of the Top End’s nature – but what would happen if our “ants” got in?

WHAT TO DO

- Explore the main highlights of Litchfield National Park on sealed roads

- Get a deeper perspective of the park on a tour with Ethical Adventures

WHERE TO EAT

- There is a cafe at Wangi Falls serving food and drink, but it would be wise to bring something with you as well

WHERE TO STAY

- There are several camping spots within Litchfield National Park, including non-powered spots for caravans

Michael Turtle was supported by Tourism Australia and Tourism Northern Territory. You can see more details on his Travel Australia Today website about Litchfield National Park.